Article courtesy of The Knoxville News Sentinel by Kristi L Nelson

Article courtesy of The Knoxville News Sentinel by Kristi L Nelson

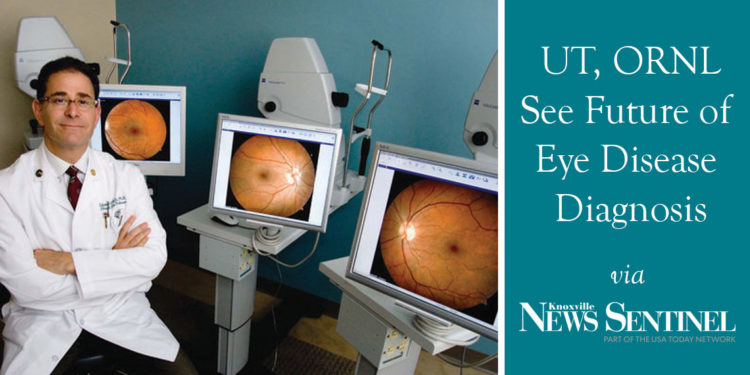

As a retinal specialist, Dr. Edward Chaum pores over hundreds of images of patients’ eyes a year, looking for diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, which can lead to blindness if not caught and treated early.

But what he sees coming in the future scares him: a predicted fivefold increase in diabetic patients over the next three decades, an onslaught of potentially diseased eyes – and not enough specialists to see them all.

Right now, fewer than half of the U.S.’s 28 million diabetics are screened for eye disease in a given year, Chaum said, in many cases because they don’t have access to screening.

Twelve years ago, Chaum, who is the Plough Foundation Professor of Retinal Diseases for the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, saw something he thought could solve the problem.

Chaum was visiting Oak Ridge National Laboratory with a group from UT and happened to end up in a seminar in which researcher Ken Tobin was talking about a computer program that scanned computer chips to find defects so they could be fixed.

If it could find defects in computer chips, he reasoned, why not eyes?

Tobin’s computer used content-basis image retrieval, in which the computer analyzed a sample looking for images from a library of more than 3,000 different types of computer defects. Popular apps today use similar technology to identify, for example, a plant or a snippet of a song.

“He’d already invented what I was thinking about,” Chaum said. “All we needed to do to teach his computers to diagnose eye disease was to change the library to a library of images of diabetic eye diseases and other eye diseases.”

Tobin was enthusiastic about the idea, Chaum said. The two started with a grant from ORNL, which they were ultimately able to leverage into a large number of federal grants to develop the technology as well as the telemedicine system necessary for it to be used in clinics and doctors’ offices.

Telemedicine – a way to scan the eyes and send the images somewhere else – made it possible for people to get their eyes scanned in places where a retinal specialist wasn’t available, but then the specialist still needed to look at the scans, Chaum said, and there aren’t enough specialists.

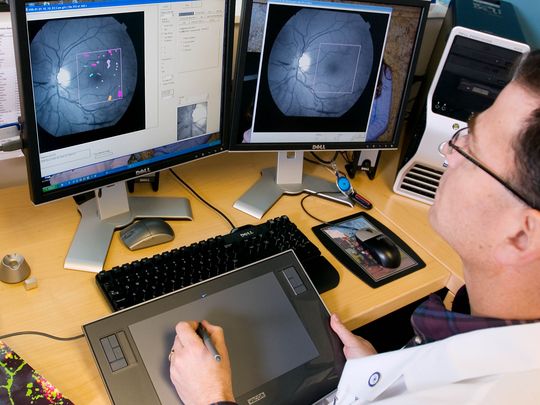

But improving technology made it possible for an automated computer program to “read” the scans – and computers don’t get tired like human doctors do. Their research team developed a program that uses the optic nerve to locate the fovea, which has the highest concentration of rods and cones in the eye, then look for tiny aneurysms and hemorrhages in the retina.

“I still had to teach the computer to think like me; there’s a difference in feature extraction and the art of medicine,” Chaum said. But “the goal and the hope is, down the road, we’ll have the ability to utilize decisions about who needs to come see a retina doctor like myself, and who can be managed with their primary-care doctor.”

Chaum and Tobin developed a start-up company, Hubble Telemedical, in 2008, and state and federal grants made it possible to take the technology into urban Memphis and the rural Mississippi Delta region, to patients who had no access to specialists. Instead, patients’ primary-care doctors took pictures of their retinas and used Hubble’s proprietary network, Telemedical Retinal Image Analysis and Diagnosis, to send the protected medical images to Hubble for doctors to analyze. Even though the computer program averaged 90 percent accuracy finding the flaws, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has specific guidelines about disease diagnosis, so until it decides the new technology is “safe and reliable,” Chaum said, doctors must confirm each of the computer program’s findings.

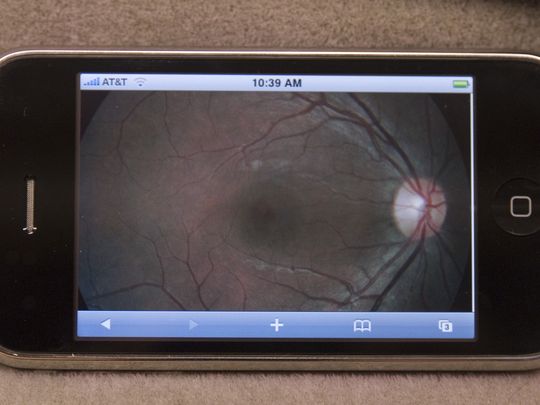

But Chaum expects patients to someday use their own smartphones to capture and transmit images of their eyes for screening.

Last year, New York-based Welch Allyn Inc., a manufacturer of medical diagnosis devices, bought Hubble Telemedical and renamed it RetinaVue Network. Chaum said he expects the technology to be FDA-approved and in wide use in five to 10 years.

“A little start-up company that operated out of my office at the university was never going to change the paradigm,” Chaum said. “But a big, international company … that’s been in the primary-care space for 100 years, they recognized a great opportunity to grow a new business and do something new and exciting. I’m thrilled to have played a role in that.”