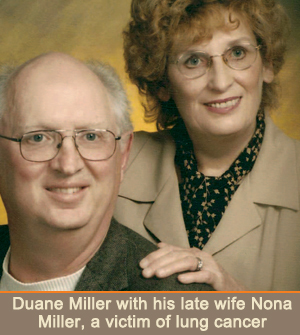

Nona Miller was diagnosed with lung cancer in June 2010. She underwent radiation and chemotherapy and was doing well, but the treatment started to take a toll on her body.

“At first she could walk around. Then she needed help up the stairs, and then she needed a wheelchair,” says her husband, Duane Miller, Van Vleet Endowed Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

For cancer patients, the disease isn’t the only issue. Miller saw his wife’s quality of life decline as her strength and energy decreased. Nona passed away in July.

Miller hopes a drug he has developed will help future cancer patients. Ostarine, under development at Memphis-based GTx, Inc., does not cure cancer, but it can be used to treat the muscle and bone wasting that affects many cancer patients.

This condition is known as cancer cachexia and is reported in about 30 percent of cancer patients, or nearly 1.3 million people, according to GTx. The need for prevention of cachexia is growing. The American Cancer Society reports that about 1.5 million new cases of cancer will be diagnosed this year.

Currently there is no treatment approved for cachexia. Ostarine would be the first.

“This would be great for the University of Tennessee and GTx, but most importantly for the patient,” Miller says.

Many relatives or friends of cancer patients have witnessed the wasting away of their bodies as they try to fight the disease. Sometimes the change in the patient’s body and strength appears worse than the effect of the disease itself.

The ability to maintain muscle mass is important for cancer patients.

“The presence of cancer cachexia is a predictor of poor treatment outcomes, increased toxicitiy in patients receiving chemotherapy, and mortality,” according to GTx.

The drug could be taken before—or along with—chemotherapy to prevent cachexia. Cancer patients have the ability to regain some of the muscle back, but prevention would be much better. Without losing as much muscle, patients would have one less condition to fight.

When Miller visited the hospital with his wife for her treatments, he took note of the other patients dealing with similar issues of muscle weakness.

“It’s horrible to watch people go through this,” he says. “We need to get (the drug) approved, so we can help them.”

Miller co-discovers SARMs

Ostarine is the first in a new class of drugs called Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators, or SARMs, initially reported in 1998 by Miller and Jim Dalton, now a vice president at GTx. Miller and Dalton were colleagues at the UT Health Science Center at the time of the discovery.

Ostarine is the first in a new class of drugs called Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators, or SARMs, initially reported in 1998 by Miller and Jim Dalton, now a vice president at GTx. Miller and Dalton were colleagues at the UT Health Science Center at the time of the discovery.

Miller earned a doctorate in medicinal chemistry at the University of Washington, where he was a National Institutes of Health fellow. He joined UTHSC in 1992 after spending 23 years at the Ohio State University. In addition to his work at UTHSC, Miller also serves as director of medicinal chemistry at GTx.

He was inducted into the American Chemical Society’s Medicinal Chemistry Hall of Fame in 2009.

“His influence has spread not only through the excellent scientific training he has provided his many Ph.D. students, but also in drug development and medicine through his involvement with GTx,” said Mitch Steiner, CEO of GTx, at the time of Miller’s induction. “Dr. Miller’s discoveries, particularly his work on SARMs, are now an integral part of our clinical development programs.”

What are SARMs?

What are SARMs?

When you think of SARMs, think of a safer version of muscle-building steroids. Because SARMs are non-steroidal, they are not associated with severe side effects such as prostate cancer and liver toxicity, and they can be taken orally.

A SARM does what it says. It selectively activates cells in certain tissues, while not affecting other parts of the body.

Androgens are hormones that affect reproduction, muscles, bones, the heart, lungs, and the central nervous system. Testosterone, known for its effects on muscles, is the main androgen for men and women. Hormones must be in balance to maintain good health.

Androgens bind with receptors in cells, allowing the androgens to carry out their purpose. With SARMs, only certain selected androgen receptors are affected and modulated. This allows Ostarine to interact beneficially with muscle and bone, yet not stimulate the prostate or liver, which could cause negative side effects.

Clinical trials

Ostarine has undergone seven clinical trials to date, with at least two additional trials and approval from the Food and Drug Administration needed before it can be made available to the public.

All of the trials so far have netted positive results. Most recently, GTx reported Ostarine to have significantly increased muscle in a head-to-head study with a SARM being perfected by the drug company Merck & Co., Inc. The drug was tested on 88 postmenopausal women over the course of 12 weeks. These results were reported in June 2010 at the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting.

In another trial, 159 cancer patients with non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma who showed signs of cancer cachexia were tested. According to GTx, “Ostarine treatment resulted in a statistically significant increase in lean body mass and improvement in physical performance, as measured by stair climb time and power.”

Another trial included 120 elderly men and women and also displayed an increase in lean body mass and muscle function. So far, Ostarine has been tested in more than 500 patients.

Uses for Ostarine

Ostarine could be used to treat other conditions aside from cancer cachexia.

Miller explains Ostarine could be beneficial for men after andropause, a male version of menopause in which testosterone levels diminish as aging progresses. It also could be used to treat muscle and bone wasting associated with menopause, end-stage renal disease, osteoporosis, and frailty.

“Muscles and bone erode a little bit as time goes on. This drug might also be useful in that situation,” Miller says. “It does slow down the aging process.”

One clinical trial demonstrated improved insulin resistance among elderly patients, which could lead to another use for the drug. GTx officials believe this result further shows Ostarine’s desired result on the body.

“By increasing muscle and decreasing fat, Ostarine appears to improve levels of glucose and insulin and to reduce insulin resistance,” says Ronald Morton, chief medical officer at GTx. “These data suggest Ostarine may have a beneficial impact on prediabetic conditions and potentially diabetes, which, if validated in later studies, could provide the basis for our seeking expanded indications for Ostarine.”

More clinical trials are expected.

“We’d like to see this on the market as soon as possible,” Miller says. “We know this will help people.”

Because SARMs produce some of the same results as steroids, they have already been banned by sports agencies. There are already ways to test for the presence of SARMs.

Ostarine’s future

While Miller developed Ostarine more than five years ago, work is continuing to advance the drug to the marketplace.

GTx expects to begin late-stage clinical trials for Ostarine in 2011. The company is looking for a pharmaceutical partner to aid in the process toward commercialization.

Meanwhile, Miller continues work on other drugs with different indications.

With three colleagues at UTHSC, Miller co-founded RxBio, a company created to license and develop drugs that offset the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy on the GI tract.

ED Laboratories, Inc., is another company Miller co-founded after the discovery of anticancer agents that treat certain types of brain and eye tumors.

Both companies’ technologies are licensed from the UT Research Foundation. For more information about GTx, visit www.gtxinc.com.